By 1870, George had decided that it was time to settle down. He had found what he believed to be an excellent location to build a home, a farm, a family and, perhaps, a community.

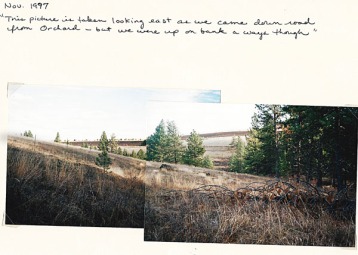

I have read the description of his search for the piece of land on which he eventually settled. In his book he says, “Following the Nez-Percé trails, (as did Lewis and Clarke [sic] the same in 1804), down across the Pataha gorge and creek, where it forks; then on a ridge, between the Pataha and breaks of the head of the Alpowa, for four miles, and here lay the spot I was looking for.” He later notes that “In one of the gulches, where the trail crossed it, there flowed, for a quarter of a mile or more, the principal spring, or springs of water for several miles around and fertile prairie land lay more adjacent to this spring, than to any other…” He lay claim to the spring and noted that he had selected land with “water, wood and grass,” on which he could build a farm and home.

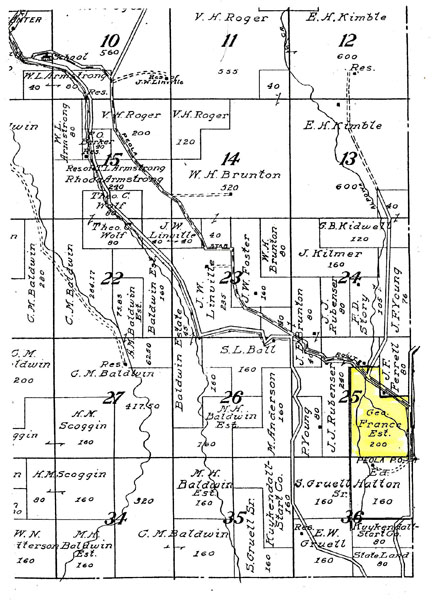

I have used Google Earth extensively to try to locate the France land and I think I have a fairly good idea where it is because Peola is at the very south-east corner. I was hoping to find something–anything–that looked like it might have been part of the France settlement 140 years ago, but to no avail. Perhaps, someday, I’ll get the chance to walk the area and look in earnest.

In 1870, George must have been in Walla Walla. In his book he talks about horses being quite cheap there and that he had decided to take the opportunity to build a small herd for himself with a view toward renting, or selling them, to the railroad folks when they came into the area. As fate would have it, Effie Cammack was also in Walla Walla, living with her mother, Albina, and stepfather, Walter Parks, who had married there in 1864. Sixteen-year-old Effie was a student at the Whitman Seminary–later to become Whitman College.

Whitman Seminary was very much an on-again-off-again affair at that time. Founded by Cushing Ells in 1859, the Seminary was floundering by 1869 . Cushing Ells was called upon to serve as principal, which he did until 1869. After Ells’ resignation in 1869, the school struggled—and often failed—to attract students, pay teachers, and stay open for each term. Family documents say that Effie, “ran away,” from the school in 1870 and it’s an easy stretch to belive that in light of the inconsistency of the school and having met George France, nine years her senior, Effie fell in love. Their marriage license is dated Sept. 13, 1871, and according to census records the marriage took place on Sept. 18.

Apparently Walter and Albina approved of the union; Walter signed the marriage license affirming the age of Effie as did H. W. Chase, County Auditor.

At first glance, it appears that all of this probably took place at the Grand Hotel in Walla Walla; “The place where the traveling man feels at home,” but as I read the hotel letterhead on which the license was hand written, I noticed that under the hotel logo in the upper left is the note that there is, “local and Long Distance Phone in every room.” This presents a paradox–Alexander Bell didn’t transmit his first call to Watson until 1876 and there certainly was no phone system in place in 1871. Hmmmm. My cursory research into the Grand Hotel found only one in Walla Walla, converted from the Ransom building to the Grand Hotel in 1911. Perhaps what we have is a photo of a hand written copy of the original? At any rate, the wedding definitely did not take place at the Grand Hotel. Perhaps the young lovers married at the home of Effies’ step-father and mother.

The France’s moved to George’s claim and into, “…a log cabin, neither spacious nor elegant, but being the best we had ever owned, it seemed to us to be both…” He noted that “the furniture would not have sold for $2.50 in a town.”

In October of 1871 George lay legal claim to the spring he had found and a quarter section of land around it. He set about breaking and planting the land, cutting timber and splitting rails for fencing, knowing that “not one in fifty” were successful in such an endeavor.

At eighteen, Effie gave birth to Clarence Gordon France on Sept. 29th, 1872. The situation into which he was born was not one of comfort and security. His Dad was still working on the land and in the spring of 1873 he planted his first crop and lost most of it to a plague of black crickets which decimated everything but potatoes and peas. The cricket plague was to continue for several years. Fortunately, he had “a good start of expensive stock-hogs,” for whom the crickets provided a feast all summer long. He had 8000 rails in fencing and started a 200 tree orchard. He hung on while most of his neighbors moved on.

In 1875 Effie Mae was born; the same year the cricket scourge ended. George had managed to hold on and, in fact, prosper a bit. “Besides farming, in 1875, I worked with my four-horse team in hauling for others, including freight from Walla Walla to the Lewiston stores.” Traveling that much left Effie, now 21, home alone with two children and a farm to watch over.

It was also in 1875 that George raised the $200 necessary to get his land patent and add it to the vacant section below what land he already had. He now had 320 acres of land and had built a 16×22 log house, a corral, sheds, and hen-house “on the best building place, at the lower spring in the spring gulch”. They moved to this hard-won spot in Sept. of 1875. While he had to go six or seven miles to get timber for fence rails, by now “I had good teams…and a wagon, was practically free of debt, had means to employee help…and there being no more insect pest…we just loped right along and ahead of the country.”

In November, Columbia County was formed from Walla Walla County, taking the France settlement with it.

1876 was a bountiful year; George threshed 1,000 bushels of wheat and Effie gave birth to their third child, Clyde LeRoy France. Beyond farming, George and Effie continued to improve their home, adding a cellar and stable, planted a garden and potato field and fenced in a pasture on the homestead claim, all of which was completed by the fall of 1878. On June 16th of that year, Effie gave birth to the last of their four children, Inez M. By now she was undoubtedly beginning to get some help from four-year-old Clarence as she went about her tasks and cared for the other three little ones.

The France’s now possessed fenced-in crops of wheat, “with plenty of grain, hay and straw to sell at good prices…barley and oats…eggs…butter…and having good herds of cattle, horses and hogs; virtually out of debt…I was ready to enlarge my home and business.”

As part of that enlargement, he broke sod on land adjoining his, which was set aside for the school. He later leased this land from the government; an action he might not have taken if he could have seen the pain and despair it would cause him in the future. The area was beginning to prosper and, since those with the grit and determination to do the hard work had done it, it became an attraction to those who wished to have what had been so hard-won without actually doing any of the difficult part themselves.

In his book, The Struggles for LIfe and Home in the Northwest, George notes that in the spring of 1878 a “Mr. E–…located a steam saw-mill a mile from my place, knowing there would be no accessible water…except be it at my place.” Somewhere in my research I came across the reference to the Ellis saw-mill and I believe it to be the mill George wrote about.

George thoroughly believed that the Masons and the Odd Fellows held the county, in fact, the whole Territory, in a strong grip and that, for the most part, the law and courts were controlled with a strong bias toward those who belonged to that organization. He believed Ellis to be a member and that he built his mill despite the fact that he “…was fully informed as to this matter before he located the mill, but turned a deaf ear; evidently having conspired at the outset to intrigue, tramp or shoot me down, and jump my place”.

True to the warning he had been given, Ellis’s mill hit the dry season and there was no water to run the steam machinery. According to George, Ellis never approached him about the use of his water, however, another man, a neighbor, requested to divert water from George’s spring and sell it to the mill. George agreed–the man quit after a couple of months and George allowed a couple of others to try it but apparently with little success.

In May of 1878 Archie Haven approached George and asked of he could put up a cabin on a corner of the school-land-tract on a temporary basis. George agreed, That was a mistake. After he had built the cabin, Haven said he had been advised by a lawyer that the law which allowed George to lease the land was invalid, therefore, he had no need to leave it or acknowledge George’s claim to it.

The France’s had spent seven years together, survived hard times, done the backbreaking work necessary and built a successful home and business. They loved, made love and created four healthy children and now trouble began that would, for all intents and purposes, put an end to all of that. Clarence was now nearly six-years-old; old enough to remember at least some of the events happening around him.

According to George, when unable to obtain a reliable water source, Ellis and “his force of men and hell [came] and stealthily put up a big tank,” took down his fence and built a pipe to the tank effectively usurping all the water for the whole settlement and posted signs claiming it as his own and threatening anyone who meddled with it. Concurrently, Haven, who frequented the Ellis mill, began again to claim the land George had allowed him to build on, claimed it to be. “an outrage for one man to own all the land in the country and the water too,” tore down fences, threatened to take the entire homestead and “settle me with an ounce of lead”. Apparently he was believed because a friend loaned George a gun with which to defend himself.

This “friend,” later told George that Ellis was a Masonic Worthy Grand Master and as such, he was bound by him to testify against George in his later trial.

When the lack of water became critical, France, who had been unable to get any help from Government representatives of any kind, busted up the pipes which were illegally hauling away his water and rebuilt his fence. When George approached a “peace officer,” (sheriff?, constable? marshal?), for assistance he received advice to ” be prepared to defend myself against him, and thus work the land.” Threats continued; life for the France’s was getting less pleasant rapidly.

On August 22nd, 1878, just over two months since the birth of Inez, George and friends/hired hands, Vasco De Lay and Bartlett Brooks set about planting wheat, part of it being on the leased school property which was in front of Archie Haven’s house. Around 11 am, Jay Lynch approached George to discuss the water for the mill issue, this discussion having the effect of slightly separating George from the other two men. It was shortly after George had refused the request for water that Lynch exclaimed, “There comes [Haven] now with a gun!”

George noted that Haven was approaching rapidly with a carbine and commented to Lynch, “…let us go and see what he is going to do with it.” Lynch replied, “I don’t give a damn what he does with it!” and hightailed it to a safe distance.

According to Roswell Fairman, who was at the Haven house at the time, Archie saw the group sowing wheat at about noon. He said as they were eating dinner Archie got up and went out, then returned, got and loaded his gun and told his wife, “there is trouble,” then left the house.

Archie Haven knew both Vasco Lay and Bartlett Brooks. He first approached Brooks and told him to take off while he could because there was going to be trouble. Brooks declined the offer. He then approached Lay and, during their conversation either pointed his rifle at him, or behind him toward George France. Lay grabbed the barrel and shoved it aside as Haven fired his first shot. Was he planning to shoot Lay, or did Lay deflect a shot meant for France? That debate was never resolved. France was not hit, but Lay’s horse was mortally wounded.

France’s first shot coincided with Haven’s second; France noted that “I emptied my pistol into him in about five seconds.” He refers to his “four” bullets–Mrs. Haven’s later testimony referred to Mr. France’s “derringer” which could quite possibly have been a four shot revolver or four barrel derringer.

This incident having taken place near the Haven home, Archie’s wife, Julia, was a witness. She ran out to help her husband and later testified that as she ran toward her husband, still struggling with Mr. Lay, she saw George shoot him as Lay held him, then saw France receiving fresh ammunition from Bartlett Brooks, who was still on horseback. France argued with Mrs. Haven and at some point Brooks apparently got off of his horse and took control Haven’s rifle. Haven had had enough, he left for home, apparently believing that he had shot France. According to George’s account, “…[Haven] went to his house, boasted that ‘he had shot my companion as well as me.'” In fact, the only person shot, if we don’t include the horse, was Archie Haven and from his actions in the field and on the way home it did not appear that he was seriously wounded.

In all of this we have no references to what Effie and the four children were doing. How far away was their house? Did they hear the ruckus? Was Effie protecting the children or trying to keep them from seeing the activity? Clarence was a month shy of his sixth birthday, he must have understood some of what happened and certainly was old enough to remember some of it. Effie Mae was three–old enough to know that something unusual was happening.

George returned home unaware that Archie was mortally wounded. Jay Lynch, who went to Haven’s house, described the wound as one which appeared to have been made by a .32 caliber ball. Dr. T. C. Frary was called and found four wounds, one in the left side; “I found upon examination one gunshot wound in the left side about 3 or 4 inches above the crest of the ileum (hipbone) from the appearance of the external wound I concluded that the ball pursued a course in the direction of the fundus of the bladder.” It was this wound, Dr. Frary concluded, that caused Haven’s death, which occurred about twenty minutes after midnight. Dr. Frary had called for assistance from Dr. D. C. Davidson, who concurred.

Unaware that Haven was dying, George decided not to file charges against him. The following day he was surprised when an official of the law arrived at his home to arrest him; Jay Lynch had filed charges for murder against George France. France was taken into custody even as he was assured that he had done nothing wrong and was sure to be freed when tried. As far as we know, this was the last time George Washington France saw Effie, Clarence, Effie Mae, Clyde and Inez.

I can only imagine the great apprehension George felt as he was parted from the woman with whom he had shared the last seven years of his life, yet, knowing he had acted in self-defense, feeling that they would soon be reunited. Then imagine how that grief must have grown as he was held for ten months without trial and it eventually became apparent that he would not see her for many years, if at all. Effie, probably with help from her mother and step father, was left to care for the four children, take care of the land and business and deal with her grief, discouragement and despair and, as it turned out, some very ill-health.

The France trial was a long time coming, may have been rigged, witnesses may have been tampered with…but that is a story for another episode.

NOTE: Much of this information was provided by Effie (France) Morris’ great granddaughter, Patricia Morris Craze and I will take this opportunity to thank her for her kind assistance which has allowed a more complete telling of this tale than could have been done without the insights she provided.